A world designed for a 24-hour cycle

I first realized just how much of our world is designed around one type of body when I read Invisible Women by Caroline Criado Perez in my undergrad. The book lays out how everything from seatbelt safety tests to office temperatures are based on male norms. And, as I later realized through my work in menstrual equity, this bias extends to how we structure time itself.

Most modern workplaces and school schedules follow a 24-hour rhythm. This matches the hormonal cycle of people assigned male at birth (AMAB). Testosterone peaks in the morning, fueling energy and focus, then gradually dips at night. This works perfectly for the way we’ve structured work into the standard 9-to-5 workday: early meetings, midday productivity peaks, and winding down in the evening.

But here’s the thing, for those assigned female at birth (AFAB) and anyone who menstruates, the hormonal landscape looks entirely different. Rather than repeating daily, it follows an average 28-day cycle with distinct phases that affect mood, energy, and mental clarity in different ways.

The 28 (ish) day reality

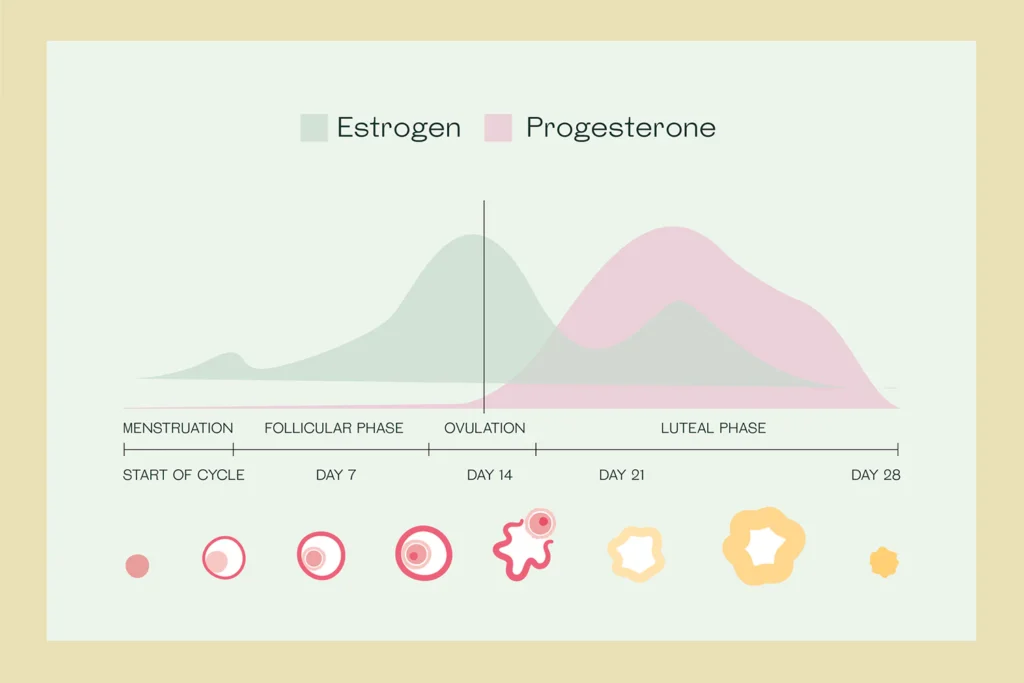

The menstrual cycle consists of distinct stages, each with their own characteristics:

The follicular phase (days ~5-13) is characterized by dominating estrogen levels, which generally brings an energy boost. It peaks with ovulation (~day 14), when you feel like you could conquer the world. Then comes the luteal phase (hello PMS), where progesterone takes over, often bringing fatigue, brain fog, and occasionally the need to eat everything in your fridge in one sitting (days ~15-28). Finally, menstruation itself (days ~1-5), when cramps kick in and both estrogen and progesterone drop, leading to a decrease in energy.

It’s important to note that these are generalizations and everyone’s cycle is unique. Some people may feel the most energetic during the luteal phase. The point is that hormonal levels fluctuate drastically over the course of a month, not a single day. Cycle tracking can help people understand these shifts and adapt accordingly. And yet, we rarely build systems that allow for that.

A system that ignores your cycle

The problem isn’t that some people have fluctuating energy levels, it’s that our systems refuse to acknowledge it. Everything from work to school assumes a linear performance model. This doesn’t account for the natural ebb and flow of energy and mental clarity that comes with the menstrual cycle.

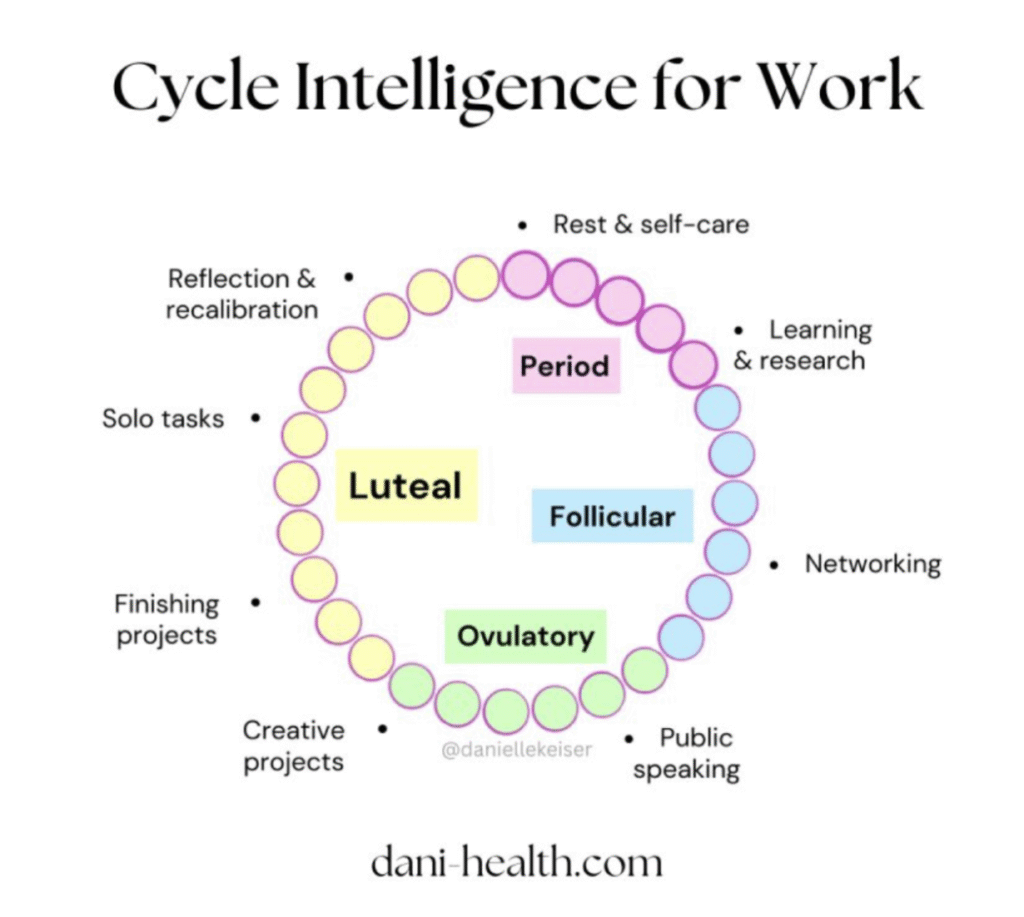

For instance, the follicular phase might be ideal for creative or high-focus tasks, while the luteal phase could lend itself to slower-paced, reflective work. Some studies suggest that during menstruation, communication between the left and right brain increases—making it an ideal time for introspection and long-term planning (1). One study even found that women soccer players performed better during their periods (2). So while physical energy may dip, mental insight might peak. And yet, the prevailing belief is that periods make you unreliable.

Despite all these fluctuations, society continues to demand the same level of productivity across all phases. I’ve lost count of the times I’ve joked with friends about how we should all be able to take “luteal phase days.” But honestly, why not? People who menstruate are expected to push through pain, exhaustion, and brain fog like it’s nothing because workplaces (and schools) weren’t built to accommodate bodies with cycles longer than a day.

And it’s not just a matter of fluctuating energy. Menstrual pain is real, and it can be debilitating. Endometriosis alone affects one in ten women worldwide and over a million people in Canada (3). Yet, people with chronic menstrual conditions are expected to use their sick days (if they even have them) to manage something that happens every single month.

So, what’s changing?

Some workplaces and governments are starting to take note. Menstrual leave policies—which allow people with severe period symptoms to take paid time off—exist in several countries. Japan was the first to introduce this policy in 1947, followed by South Korea in 1953. Other countries such as Indonesia (2003), Taiwan (2002), and Zambia (2015) have enacted similar policies. Most recently, Spain became the first Western country to implement paid menstrual leave in 2023 (4). While Canada hasn’t implemented a national menstrual leave policy, some private companies have taken the lead in this area. For instance, DIVA offers 12 Paid Menstrual and Menopause Leave days per year, with 1 day allowed per cycle (5).

However, just because a policy exists doesn’t mean people actually use it. In Japan, less than 10% of female employees use this leave. Reasons include societal stigma and discomfort discussing periods with male supervisors. The workplace culture also discourages menstrual-related time off. (6). In South Korea and Indonesia, employees report that their requests are frequently denied. Zambia even refers to its policy as “Mother’s Day,” reinforcing the (incorrect) idea that menstruation is only a concern for mothers (7).

It’s clear that menstrual leave alone won’t fix the problem. What’s really needed is a culture shift, one that treats hormonal cycles as a normal part of life rather than an inconvenience to be ignored. That means normalizing conversations about menstruation, offering period products in schools and workplaces, and providing more flexible work arrangements so people can function at their best, rather than forcing themselves to perform at their worst (8).

This isn’t just about menstruation, either. Hormonal variations affect everyone, whether due to testosterone, estrogen, progesterone, or other factors like gender-affirming treatments, pregnancy, or menopause. People of all genders experience hormonal fluctuations that influence their physical and mental well-being. The point is, our systems should work for people, not the other way around.

So maybe the question isn’t, “Why do I feel off some days?” but rather, “Why is everything structured for just one type of hormonal rhythm?”

And maybe, just maybe, it’s time for a change.